Canada is not a poor country, and therefore can afford good road infrastructure. How does she build her roads? What makes them different from Russian ones? Let's try to answer these and other questions.

A bit of history

Canada's first transportation routes were rivers and lakes, used by indigenous peoples for canoeing in summer and frozen waterways in winter. The water service proved to be so practical that explorers, settlers and soldiers followed the example of the indigenous peoples.

Until the 19th century, the construction of roads was insignificant - they only supplemented, and did not replace, the water network, providing internal movement (especially in winter) and opening up new areas for settlement. Basically, these were cleared earthen paths, some were paved with logs. Only city streets were lined with cobblestones.

Traveling in early Canada by transport was difficult and often dangerous, with people preferring to travel on horseback or on foot. The settlers' carts were homemade and crude, the wheels carved from the round trunks of huge oak trees. Later, 4-wheeled flatbed carriages and Conestoga vans for the transportation of heavy loads appeared (6-horse teams up to 9 m long), and the elite of new cities and villages acquired open carriages.

In the era of stagecoaches, stretching over 50 years from the early 19th century, regular passengers and mail began to be transported domestically and abroad, but traveling in inconvenient means of transportation, from covered vans to clumsy carriages suspended from leather springs, remained an adventure. In winter, they were installed on runners, some were equipped with wood-burning stoves for heat.

With the advent of trains, the era of stagecoaches fell into decay. The roads began to be used only for local travel, and their condition gradually deteriorated - with huge investments in railways, there was practically no money left for ordinary roads.

Gold was discovered in Hope in the late 1850s, and hordes of miners poured through the Fraser and Thompson river valleys to the Caribou. Roads were needed to service the rapidly growing townships. Royal Engineers and private contractors, having hired unlucky miners as labor, built Cariboo Road in 3 years at a cost of $ 2 million. It was one of the wonders of its time, crossing gorges on suspension bridges and overhanging cliffs with log overpasses.

Rapid transport development began with the construction of the Alaska Highway during World War II. In 1958, the Diefenbaker government introduced the Roads to Resources program designed to exploit the natural resources of the North, and traffic began to increase every year, with supplies and mining equipment moving north while minerals, fish and fur moved south. In some provinces, funds were also allocated for the development of tourism: over 8 years, $ 145 million was spent on the construction of 6400 km of tourist roads.

Development of road communications

The modern motorway system dates from the advent of the internal combustion engine. In 1898, John Moody from Hamilton brought the Winton single-cylinder horseless carriage from the United States. Six years later, a Ford assembly plant was erected in Windsor, Ontario, and the Canadian auto industry was born.

In 1907, 2,131 cars were registered in the country, by the beginning of the First World War - more than 50,000. It took some efforts to improve roads and streets. In 1914, the first road department appeared. Two years later, Ontario, home to a special road construction instructor attached to the Department of Agriculture since 1896, formed its own separate highways department.

In the 1920s, cars began to fall in price, and by the end of the decade, their number had grown to 1.62 million. Road associations, national and provincial, have spearheaded a crusade to improve road traffic, and government spending on roads has tripled. By 1930, the cost was $ 94 million. As technology improved, horse-drawn vehicles gave way to steam scrapers, graders and rollers. During the Great Depression and World War II, construction was reduced to a minimum - the war required people and equipment, and freshly built paved roads were destroyed by heavy military traffic, especially in industrial areas.

The post-war period did not leave any aspect of economic or social life unchanged. With the development of technology, the network of highways and streets for road transport expanded. Highway spending rose from $ 103.5 million in 1946 to $ 4.5 billion in 1986, surpassing $ 6 billion by the beginning of the 21st century.

In 1946, there were 28,982 km of rural and 10,000 km of paved urban roads, fifty years later Canada had a total of 901,903 km of public roads, including 442,408 km of gravel roads, 301,348 km of paved roads and 16,571 km of motorways. These changes have left a deep mark on the Canadian landscape, transforming the environment with expressways, interchanges and development along the highway.

Engineering and jurisdiction

Early traffic rules were simple: bells on harnesses were used to warn of approaching carts in poor visibility, and road markings were carried out using evergreens. With the advent of cars, identifying color stripes began to be applied to telephone poles, and motorway numbering was introduced only in 1920.

In 1930, an engineer in Ontario experimented with white dotted lines along the center of the road, and within three years they became the standard for the entire continent. Since the 1940s, municipalities have been actively recruiting professionals with experience in planning and electronics to unravel road problems.

In 1956, the Canadian Good Roads Association established the Council for Unified Traffic Control Devices and published the first guide to signs, signals and pavement markings three years later. The association has also launched a scholarship program to help overcome skill shortages to introduce new construction techniques and computer programming.

By 1995, there were 655,892 km of public roads in the municipal jurisdiction, 230,930 km in the provincial, and 15,082 km in the federal one. User revenue - taxes on fuel and vehicles, driver's licenses, fines and street parking fees - has never been enough to cover the costs. Federal money was used to fund territorial funds from the Canadian Transportation Agency, the Transportation Safety Board, and other federal agencies, including aviation, fisheries, municipal services, and national parks. Large sums to this day come from consolidated revenues, based on the logical belief that efficient road transport infrastructure benefits the entire economy.

Modern Canadian roads

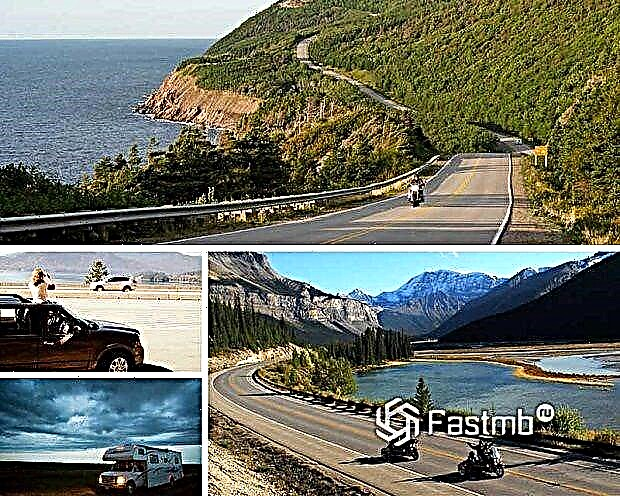

Today in Canada there are more than 1 million km of roads, of which 415,600 km are paved. Prioritize safety: lighting, wheelchair ramps and gutters, guardrails in hazardous areas, curbs or wide swaths along the edges of the highway that make the car shake to shake a distraught motorist.

The roadside service is well developed - from repair and rescue services and gas stations to recreation pavilions, fast food outlets, toilets and shops. Autobahns, highways and streets are constantly being built and reconstructed.In places with heavy traffic, work is carried out at night when the traffic load decreases.

In addition to road construction and maintenance, the tasks of road services include:

- highly visible and durable road markings (paint and thermoplastic);

- signboards, signs, cameras, traffic control systems;

- installation / dismantling, restoration, modernization and maintenance of underground utilities and pipelines;

- development and implementation of new design and construction methods, cover materials and specialized products.

Why roads in Canada are better than Russian ones

Canada has one of the most powerful economies in the world and remains at the forefront of technology, not only taking advantage of other people's developments, but also producing its own advanced products.

Several years ago, the country embarked on an ambitious program, whose key component was the use of technologies that improve the environmental friendliness and durability of the road surface. These include innovative asphalts like EcoMat, which is produced at temperatures lower than traditional ones, mixes like Fibermat using chopped fiberglass sealing and anti-cracking strands, Coletanche bitumen geomembranes, geotextiles and geogrids.

One of the most promising techniques uses short 20 mm co-extruded polyolefin cores about 0.3 mm in diameter with a special coating.

Imagine an electrical wire with a copper strand wrapped in plastic. In this case, the insulator is a nano-coating that is activated by moisture to seal and “cure” the concrete in which it is embedded. These strands are added to the concrete mix and form a random 3D mesh inside. This gives strength in several ways at once: cracks do not have a path along which they can move, because the threads impede their progress; at the same time, any moisture that penetrates the concrete immediately activates the nanocoating, forming calcium silicate hydrate and initiating the self-healing process.

Yes, the costs due to fibers increase by 33%, but concrete is consumed by a third less with the same paving depth as traditional roads, and the service life is at least three times longer. Withstanding five seasons of rain and frost, the coating remains as smooth as on the day of installation. In addition, the mixture is 60% power plant ash and recycled tire fibers, so the carbon footprint is reduced by a third, and in the process, billions of tires that cannot be recycled can be disposed of.

The general condition of the roadway in Canada is better than in Russia, although its condition varies greatly depending on the season, and many potholes form after winter. But problem areas are restored in a short time. And the Canadians do not save on construction: less than a million dollars per kilometer of motorway in Russia, in Canada - up to 2.7 million.

In addition, specific people are responsible for quality - from designers to contractors, and control is carried out by an independent expert examination, which excludes the possibility of collusion between the persons involved in the project. Bad faith is punished inevitably and quickly.

Russian road builders are in no hurry to invest in revising obsolete construction standards, modernizing production and innovative technologies. Defects in laying and quick cracking of the upper layer of the road, saving on equipment, materials and specialists in Russia is perceived as the norm, not to mention the banal embezzlement of funds, which drags on for years of repair and construction work and unsuccessful search for the culprits. In the best case, individual links are being improved, and not the entire technological chain, as it should be.

Plus, contractual tenders and the accompanying kickback system make it difficult for bona fide contractors to get through to projects. There is also a problem with financing - even official sources confirm that it does not take place in full, but in small tranches. Moreover, the money simply does not reach the regions, going into pockets and patching up small-town social holes with the remnants.

Conclusion

Judging by the feedback from Canadians and Russians, there is plenty of dirt and potholes everywhere. But the difference is that in Canada, roads are better built, better equipped and restored faster, tenders are open, contractors are responsible, and road workers are paid decent wages and do not take hour-long breaks eight times a day. And if we evaluate the quality of roads not by egregious cases, but by the "weighted average" condition, it must be admitted that in Canada it is indeed much higher.

|| list |

- A bit of history

- Development of road communications

- Engineering and jurisdiction

- Modern Canadian roads

- Why roads in Canada are better than Russian ones